If people know anything at all about Titus Andronicus, it’s probably that the final scene involves an episode of cannibalism, where two sons are baked into a pie and served to their mother at dinner. However debauched you might think the current age, it’s pretty unsual to see such a scene in today’s theatre. It also explains why Titus has gained a reputation as a bad play (for ‘bad’ read ‘distasteful’). However, as most people will find, Titus Andronicus is a fascinating play. Not only is it a pacy study of power and inhumanity, it prefigures Coriolanus and Julius Caesar, and has a lot in common with King Lear.

I’m not saying there aren’t crude elements to it, or bits that aren’t trying to imitate Christopher Marlowe, but as Professor Jonathan Bate has pointed out, Titus Andronicus did the most to establish Shakespeare’s career as a playwright. It’s also been surprisingly popular in recent times:

… on the few occasions when it has reappeared in the repertory it has repeated its orginal success: Peter Brook’s production with Laurence Olivier as Titus was one of the great theatrical experiences of the 1950s and Deborah Warner’s with Brian Cox was the most highly acclaimed Shakespeare production of the 1980s.1

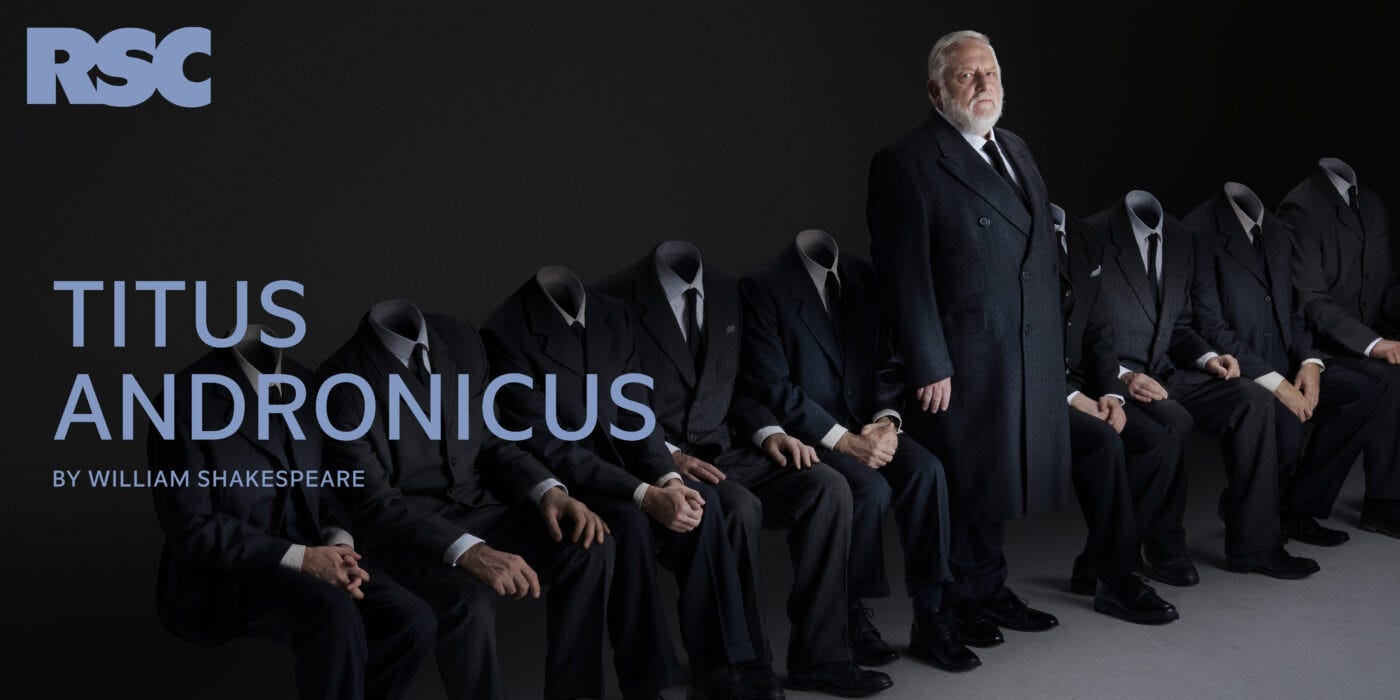

Certainly, the current RSC production, with Simon Russell Beale in the title role, is getting enthusiastic responses - on the night I attended, it received a standing ovation. Directed by Max Webster, the piece is set in an undefined period, though - much like experience of reading the play - your mind supplies all kinds of contemporary parallels. To construct the plot, Shakespeare used several classical sources - the story of Philomel in Ovid’s Metamorphosis and possibly the tragedies of Seneca - but it’s not necessary to know them to follow the action.

Firstly, we meet Titus Andronicus - a victorious Roman general - as he comes home from the war with the Goths. He has lost many sons on the battlefield, but also brings with him some prisoners, including Tamora, Queen of the Goths, and her three sons. In order to placate the ghost of his own dead son (whose body he is about to inter in the family tomb), he decides to have Tamora’s eldest son, Alarbus, killed and sacrificed to the gods. This is a pivotal moment of the play, which (in my opinion) sets off the whole tragedy:

Tamora [kneeling]: Victorious Titus, rue the tears I shed,

A mother’s tears in passion for her son!

… Sweet mercy is nobility’s true badge:

Thrice noble Titus, spare my first-born son.

That “Sweet mercy is nobility’s true badge” reminds me so much of Portia’s “quality of Mercy” speech in The Merchant of Venice. Anyway, Titus ignores her pleas and directs one of his sons to “hew” the limbs of Alarbus, which he does.

This drama unfolds against another, larger one which will establish the leadership of Rome. With the Emperor having died, his two sons, Saturninus and Bassianus, are competing for the position. Yet Titus is very popular with the people, and, encouraged by Titus’s brother, Marcus, they offer him the throne instead. However, as Titus explains, he doesn’t want it:

Give me a staff of honour for mine age,

But not a sceptre to control the world.

When asked by the people who they should choose, Titus does the ‘right’ thing and names Saturninus, since he is the eldest son. Once in power, however, Saturninus can’t resist a final insult to his brother, naming Titus’s daughter, Lavinia, as his wife - despite the fact that she is betrothed to Bassianus. However, this doesn’t last long because Saturninus is soon attracted to Titus’s prisoner, Tamora, and ends up marrying her instead. This is not only an insult to Titus - it puts Tamora in a position of power where she can wreak revenge on her former captor.

Meanwhile, we learn that Tamora is having a clandestine affair with a Goth - Aaron the Moor - whose talent for extreme violence comes in handy and helps to propel the rest of the action. With his connivance, Bassianus is murdered and Titus’s daughter, Lavinia, is captured by Tamora’s sons and raped. In order to prevent her from naming them, they cut off her tongue and hands.

The rest of the play is a chain of violence which I won’t reveal, but if you can get tickets to see the RSC production, you will see that Webster has not shied away from presenting it realistically. We had seats on the second row of the stalls, and were bemused to see splash guards, drip trays and blankets for the people in front, to protect their clothes. During the action, the actors sprayed ‘blood’ from hoses which dropped form the ceiling, and we saw a severed hand and two heads in bags.

If I had to pick one book to read alongside Titus Andronicus it would probably be Niccolo Machiavelli’s The Prince.2 This 16th-century Italian treatise was supposedly written to help Machiavelli’s patron, Lorenzo de Medici, hold onto power, and deals with thorny issues such as ‘Is it better to be loved or hated?’ and ‘How should I deal with my subjects?’ On its publication in 1532, it shocked many readers because it apparently argues that immoral acts are justifiable in the name of political glory (now termed realpolitik).

It’s not clear whether or not Shakespeare read The Prince, but he would certainly have been familiar with the ‘Machiavel’ character: typically a pitiless rogue (Aaron and Iago are both examples, as is Marlowe’s Barabas in The Jew of Malta). A fun way to read it is to imagine Machiavelli giving advice to Shakespeare’s characters in Titus Andronicus.

In the case of Saturninus, he has the following to say:

… a prince is always compelled to injure those who have made him a new ruler, subjecting them to the troops and imposing the endless other hardships which his new conquest entails. As a result you are opposed by all those you have injured in occupying the principality, and you cannot keep the friendship of those who have put you there; you cannot satisfy them in the way they had taken for granted, yet you cannot use strong medicine on them, as you are in their debt.3

This is, of course, the problem that Saturninus finds himself in with Titus - he is in the general’s debt and he also fears him because Titus is loved by the people.

Machiavelli also has some advice for Titus:

… when a prince is campaiging with his soldiers and is in command of a large army then he need not worry about having a reputation for cruelty; because, without such a reputation, no army was ever kept united and disciplined.4

Perhaps when Titus killed the Queen’s son, Alarbus, his mistake was to act as he would have done with his troops rather than at home? Certainly, at the start of the play we see him make several mistakes: firstly, he refuses to be merciful with Tamora, and, secondly, he rejects the throne.

There is a third decision of Titus’s which may seem, to us, deranged. At the start of the play, he kills his own son (Mutius) for barring his way during a dispute. At the RSC this scene was cut, probably because it undermines our sympathy for Titus, but it does tell us something important. To Shakespeare’s classically-trained audience, it would have reminded them of a real politician and general called Titus Manlius Imperiosus Torquatus: a man who was consul three times and who killed his own son on the battlefield for disobeying his orders.5 Far from being criticised, Manlius was worshipped by the people, who knew he would put Rome before his own family.

In the example above, we can see Shakespeare complicating our moral reactions - just as Machiavelli does in The Prince. In fact, one of the biggest ironies of Titus Andronicus is that the truly awful people get into power, while the ones who should wield it are not interested. It’s a bit like what Bertrand Russell said about the fools and fanatics always being so certain of themselves, while the wiser people are full of doubts.

Titus Andronicus runs at The Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until June 7th 2025.

Jonathan Bate, Introduction, Titus Andronicus (Arden, 2023), p. 1.

OK, the obvious choice is Ovid’s Metamorphoses - but the Philomela story is only a few pages, so you could easily read that as well!

I am quoting from the George Bull translation of The Prince (Penguin Books, 2004), p. 7.

Ibid., p. 72.

Thany you to Richard Bratby for pointing out this parallel. Presumably Manlius was Shakespeare’s model for Titus Andronicus.

Ah fresh back into bloodbaths that is ever the potential of Politics to set flowing in furious gory spate. Written so long ago, Titus A and The P, yet so worthwhile as references for "we few, we literate and reducing few" to read on the page or follow in performance to reflect awhile and them ruminate further on in our bloodletting times.

Thoughtful post. Thanks you.