I’ve revisited an article from my blog archive describing how myself and my husband toured Leeds in May 2010, looking for remnants of the 18th-century city.

Well, it’s been some time since my Georgian Liverpool series and a trip, last weekend, to see Opera North in Leeds proved to be the perfect opportunity to investigate another modern British city, looking for the traces of its 18th-century heritage.

Even though Leeds was a prosperous centre for woollen-cloth manufacture in the Georgian period, 18th-century traces were much harder to spot here than in Liverpool. Perhaps this is because we know Liverpool better, but also because Leeds - like Birmingham - is essentially a 19th-century city, packed with the Victorian buildings, wharves and warehouses.

In A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724, above), Daniel Defoe wrote down some of his observations of the city as follows:

Leeds is a large, wealthy and populous town, it stands on the north bank of the River Aire, or rather on both sides of the river, for there is a large suburb or part of the town on the south side of the river, and the whole is joined by a stately and prodigiously strong stone bridge, so large, and so wide, that formerly the cloth market was on the bridge itself. The increase in the manufacturers and of the trade, soon made the market too great to be confined to the bridge, and it is now kept in the high street [Briggate], beginning from the bridge, and running up north almost to the market house, where the ordinary market for provisions begin.

The market is here twice a week. At seven the market bell rings (in the summer earlier, in the depth of winter a little later). It would surprise a stranger to see in how a few minutes, without hurry or noise, and not the least disorder, the whole market is filled; all the boards upon the tressels are covered with cloth, close to one another as the pieces can lie long ways by one another, and behind every piece of cloth, the clothier standing to sell it.

Merchants in Leeds go all over England with droves of pack horses, and to all the fairs and market towns all over the whole island. Other buyers of cloth send it to London. They not only supply shopkeepers and wholesale men in London but for exportation to the English colonies in America and to merchants in Russia, Sweden, Holland and Germany.

It wasn’t always plain sailing for 18th-century wool merchants in the north of England, since cash was in short supply and the markets could be volatile. Nevertheless, the waterways (including the Leeds to Liverpool canal, built 1770-1816) were a major catalyst for the growth of Leeds as an industrial centre. As Defoe noted, it was the movement of the cloth market from the bridge into Briggate itself in 1684 that created the beginnings of the city of Leeds as we know it. It soon became a prosperous city, with the population (10,000 at the end of the 17th century) soaring to 30,000 by the end of the 18th. The Aire and the Calder rivers were made navigable, putting the Ouse, Humber and the sea in reach and propelling Leeds into the heart of the Industrial Revolution.

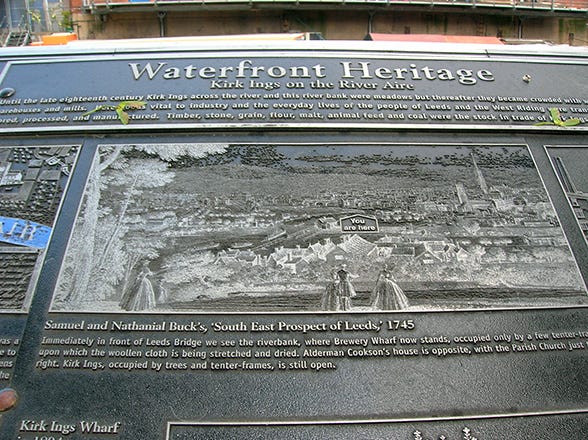

Walking beside the river, we found a couple of interpretive panels including the one above showing Samuel and Nathaniel Buck's South East Prospect of Leeds from 1745; the figures look out on fields full of tenter-frames on which the woollen cloth would have been dried and stretched. There was also a copy of the first map of Leeds by John Cossins in 1725 titled, A New and Exact Plan of the Town of Leedes. Perhaps the most interesting building in this area, though, is Fletland Mills: a collection of late 18th-and 19th-century mills that sprawl along the wharfside. Bought in 1887 by Wright Bros, the complex is now 42 The Calls (an upmarket hotel and restaurant). Just a glance at the back of the building (below) shows its antiquity.

I can’t help feeling sad for Leeds Assembly Rooms. In the late 18th century it was a glorious venue where balls and card parties were held for prosperous merchant families, now it feels slightly down-at-heel. The railway – which was extended through the town in 1865 – destroyed the grandeur of the building, though attempts have been made to jazz-up the area (now known as the Exchange Quarter).

The life of The Assembly Rooms began in 1777, when Sir George Savile and Lady Effingham launched them on an upper floor of the third white-cloth hall.1 Thanks to some sensitive restoration you can still see the front of this building (above). It was planned by wealthy Leeds merchants – spurred on by the opening of a rival cloth hall at Gomersal – and built on the Tenter Ground in the Calls. The original structure was two storeys high at the northern end and constructed around a large central courtyard. Public events were sometimes staged in the courtyard, such as a balloon ascent by the Italian aeronaut, Vincenzo Lunardi, in 1786. Known as “The Daredevil Aeronaut”, Lunardi staged several events in England but fled abroad in 1786 after one of his stunts ended in a fatality.

The cupola you can see in my photograph actually comes from the second white-cloth hall, and was installed in 1786. When the above building was restored in 1991, a small bell was put inside - it’s struck by an internal electric clock hammer (though rarely sounds now).

With the coming of the railway in 1865, the people of Leeds had to build a fourth white-cloth hall because the North Eastern Viaduct literally sliced the New Assembly Rooms in half (the railway company did foot the bill for the new building). Yet, due to the decline in cloth manufactuting, this fourth hall was never fully used and ended up being demolished in 1895. Today the site is occupied by a hotel. However, like the second white-cloth hall, the original building's cupola was retained and incorporated into the new roof by the city’s thrifty locals.

While you’re here I wanted to let you know that I’ve started a new addition to my Substack publication: The Lichfield Rambler subscriber chat. I’ll use this to post questions and updates - I’ve posted one already about my plans to develop this publication. If there are particular topics you would like me to write about, I’d love to hear from you!

As the name suggests, the white-cloth hall sold undyed cloth, whereas the mixed or coloured-cloth-makers used the market in Briggate.

Most interesting, thank you.