Addison's Walk

And the Pleasures of the Imagination

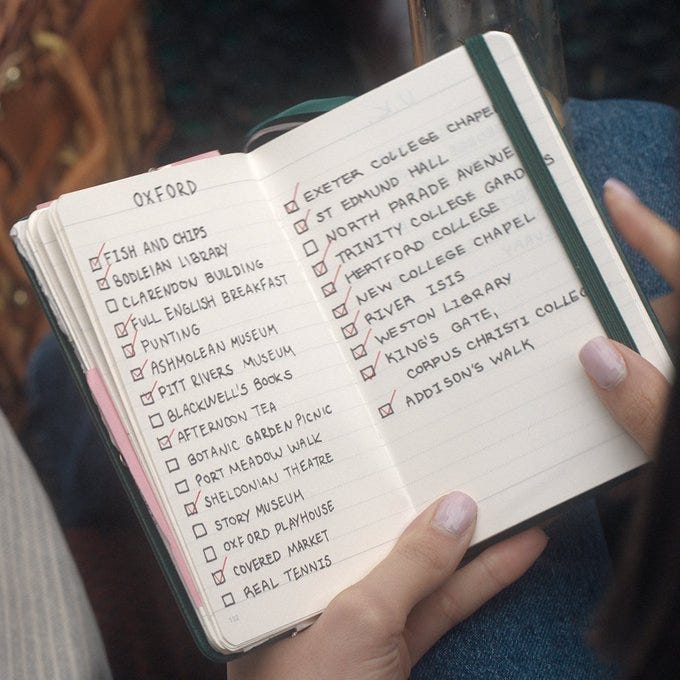

You may have noticed the existence of a naff romantic comedy-drama recently on Netflix called My Oxford Year. It was a momentary sensation for two reasons: a) it made some hilarous mistakes about Oxford and b) the main character had a checklist of things which she wanted to achieve during her time studying her Masters in English Literature at Magdalen College.1 It was harmless nonsense which added to the the gaiety of nations, but while I was laughing at the checklist (below), I noticed Addison’s Walk.

My husband - an Oxford graduate - had heard of it but confessed that he had never visited, manly because he didn’t know people at Magdalen when he was a student. I was spending a lot of time writing about Joseph Addison and his journalist partner, Richard Steele - founders of The Spectator - so, naturally, I was curious. We decided to tick Addison’s Walk off our own checklists.

The path - with its views of the private deer park and Magdalen Tower - has been popular since at least the 1600s; then the area was known as the ‘Water Walks’, and it’s by this name that Addison would have known it.2 Today, the path winds around a small island in the River Cherwell, but the route originally finished at an old Civil War gun position, Dover Pier, on the river.3

I found the following details in a 19th-century biography of Steele which explains its popularity:

Loggan, in his Oxonia Illustrata (1675), gives bird’s-eye views of all the colleges as they appeared [at the close of the seventeenth century]. The Gardens were, as a rule, laid out in a formal, rectangular style; at Christ Church there were several gardens of this kind, and in the adjoining meadows we can trace the beginning of the Broad Walk - “Ambulacra, the Walks”. But the grounds at the rear of Magdalen College were then more popular, and Addison has left a Latin poem, [Sphaeristerium], upon the Magdalen bowling-green. Tickell, in his poem on Oxford, speaks of “Magdalen’s peaceful bowers”, where “every muse was fond of Addison”.4

Magdalen’s grounds really came into their own around 1717, at the height of Addison’s career (in that year, an Oxford student paid tribute to him as the “Great Patron of our Isis groves, Whom Brunswick honours and Britannia loves”).5 The reason for Magdalen’s increased popularity was due to the locking of Merton’s garden door “on account of its being too much frequented by young scholars and ladies on Sunday nights”. After this closure, people crowded into Magdalen’s paths, and - by 1723 - they were “just like a fair”.6

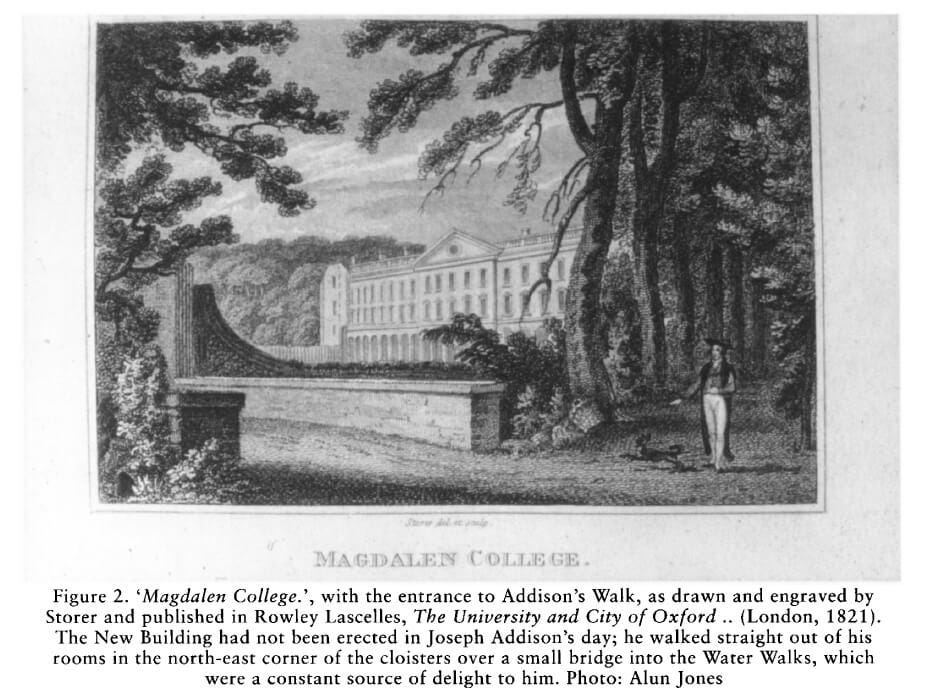

Addison was a student at Magdalen from 1689, and a Fellow between 1698 and 1711. He was distinguished for many things, including penning the play Cato and briefly becoming Secretary of State, but he is chiefly remembered as a journalist and essayist (one biographer went so far as to call him the “chief architect of Public Opinon in the eighteenth century”).7 His Kit-Cat Club portrait (above) shows him as a sophisticated urbanite, polished and elegant, but he had another side to his personality which responded to nature and country pursuits. At his Tudor-era villa, Bilton Hall in Warwickshire, he remodelled the grounds, making space for over a thousand trees - as he told Alexander Pope, he “[took] much pleasure” in the time spent working in nature.8

Pleasure is a key topic in Addison’s writing. In the 1690s, while still at Oxford, he began writing essays which would later find their way into The Spectator as a series called ‘The Pleasures of the Imagination’ (1712). Addison formulted these pieces - inspired by Locke’s ‘Essay Concerning Human Understanding’ (1690) - while striding around Magdalen’s walks. Like Locke, Addison believed that knowledge is derived from sensory perception and experience. He developed this theme by considering the role of nature in sharpening the imagination, especially amongst poets. In the manuscript version of Spectator No. 417 he wrote:

[The writer] must love to hide himself in Woods and to haunt the Springs and Meadows. His head must be full of the Humming of Bees, the bleating of the Flocks and the melody of Birds. The verdure of the Grass, Embroidery of the Flowers and the Glist’ning of the Dew must be painted strong in his Imagination.9

In the 1760s, William Mason - who was gathering material for his long poem, The English Garden - claimed that Addison had invented a new style of gardening. This had emerged from the ‘Pleasures of the Imagination’ essays, particularly No. 414, in which Addison explained that formal gardens could only please so much because the imagination runs quickly over them.10 In the “wild Fields of Nature” on the other hand:

… the Sight wanders up and down without Confinement, and is fed with an infinite variety of Images, without any certain Stint or Number.11

This ocular liberty, Addison realised, was “more delightful than any artificial shows”. It also explained why English gardens were not as entertaining as those in France and Italy, where “we see a large Extent of Ground covered over with an agreeable Mixture of Garden and Forest, which represent everwhere an artificial Rudeness, much more charming than that Neatness and Elegancy which we meet with in those of our own Country”. Queen Caroline - who knew and admired Addison - summarised his approach as “helping Nature and not losing it in art”.

Addison’s ideas would go on to influence major landscape gardeners such as William Kent and Capability Brown, but it was in the Water Walks at Magdalen that he first developed a “due Relish for the works of Nature”. Today, both the natural (forest) and the formal (deer park) can be appreciated from a convenient stone seat about halfway along the path which is marked by a pair of ornamental iron gates. These gates are worth a closer look because they come from Bilton Hall and bear the initials of Addison and his wife: Charlotte, Countess of Warwick.

A few of my photos are below, sadly I forgot to take any of the deer park!

Mistake number one: the M.A. is an ad eundem degree at Oxford, which means you are not required to study for it.

I seem to remember that the path beside the cathedral in Lichfield was also called Addison’s Walk (the writer’s father, Lancelot Addison, became dean of Lichfield Cathedral in 1683) but I have not been able to find any written references to it.

The Victorians renamed it Addison’s Walk as a protective measure following a controversial proposal by Humphry Repton to landscape the area and float a lake in the meadow.

George Atherton Aitken, The Life of Richard Steele, vol. 1, pp. 38-9.

Congratulatory Epistle to the Rt Hon Addison by a Student of Oxford 1717.

George Atherton Aitken, Op. cit., p. 40.

Stephen Miller, ‘The Strange Career of Joseph Addison’, The Sewanee Review, Autumn 2014, Vol. 122, No. 4, p. 650.

Sean Silver, ‘Addison’s Walk’, The Mind is a Collection.

Quoted in Mavis Batey, ‘The Pleasures of the Imagination: Joseph Addison’s Influence on Early Landscape Gardens’, Garden History, Autumn, 2005, Vol. 33, No. 2 (Autumn, 2005), p. 192.

Ibid., p. 190.

Joseph Addison, The Spectator No. 414.

This article seems to me to be a perfect use of Substack, Annette! I really enjoyed it.