"A Big Job for Very Little Cash!"

Tarot: Origins and Afterlives at the Warburg Institute, London

I had hoped to get this piece out sooner, before the Tarot - Origins & Afterlives exhibtion closed at the Warburg Institute on April 30th 2025, but I had not anticipated how difficult it would be to get tickets (I ended up going in the week, not long before it closed). Anyway, as it was the first major exhibition on tarot in the UK, I’ve written it up and included my photographs for those who are interested.

Many people think - incorrectly - that tarot was invented by the ancient Egyptians, but as the exhibition made clear, this was a myth devloped by French esotericists in the 18th century. In fact, tarot emerged in Northern Italy during the 15th century, as a game (tarocchi), although people were probably using the cards for fortune telling almost immediately. The oldest surviving deck was made for the Dukes of Milan and is known as the Visconti-Sforza.1 I had regarded this as a bit of a unicorn deck - it is famously elaborate (hand-painted and gilded) - so it was a real treat to see examples on display at the Warburg.

After the Visconti-Sforza, the next major turning point for tarot was the invasion of the French into Northern Italy in the early 16th century. They brought with them a deck which we now call the Tarot de Marseille, and which is the foundation of every deck out there today. The earliest version is thought to have been made by Jean Noblet around 1650, but other theories abound as to its origins (the exhibition claimed 1639 as the date of the earliest surviving example).

This tarot is similar to a modern playing-card deck, in that it has numbered cards in suits (the ‘minor arcana’) plus court cards (in this case: queens, kings, knights and pages), but, unlike playing cards, it also comes with 22 named cards (the ‘major arcana’) which are numbered 0 to 21.2 In tarot-speak, the major arcana are known as ‘trumps’ and the minor arcana, ‘pips’. There are many theories about how the trump cards came into being, but they appear to stem from another system - probably Carta da Trionfi (Triumph cards) - a game referred to by the Duke of Ferrara in 1442.3

Once it had entered Italy, the Tarot de Marseille had a strong influence on the both the development of playing cards and fortune telling. In fact, the discovery of some old Marseille cards during the cleaning of wells and water tanks in the Sforza Castle, Milan, shows that they were adopted early on. Nobody knows how they got into the Castle’s water system, but they were clearly popular!

Tarot took another leap forward in the 18th century, thanks to the work of several French occultists. Firstly, there was Antoine Court de Gébelin, who published essays on tarot by himself and Le Comte de Mellet in 1781. Gébelin and Melet appear to be the source of the Egyptian mythology, and they were also the first to associate tarot trumps with letters of the Hebrew alphabet.

They were closely followed by Jean-Baptiste Alliette, who published the first systematic approach to cartomancy, Manière de se récréer avec le jeu de cartes nommées tarots (“A Way of Entertaining Yourself with a Deck of Cards”) between 1783 to 1785. The latter - who styled himself “Etteilla” (which is Alliette spelt backwards) - pioneered the idea of reading reversals (i.e., cards that fall upside down). He also invented the practice of laying cards out in a pattern (known as a “spread”). He used a 32-card Piquet deck, a standard French-suited deck with cards two to six removed from each suit, and he added an extra card, a significator he called “Etteilla”. He also produced his own deck, known as the Petit Etteilla, later used by Madame Lenormand: a celebrity cartomancer of the Napoleonic era.4

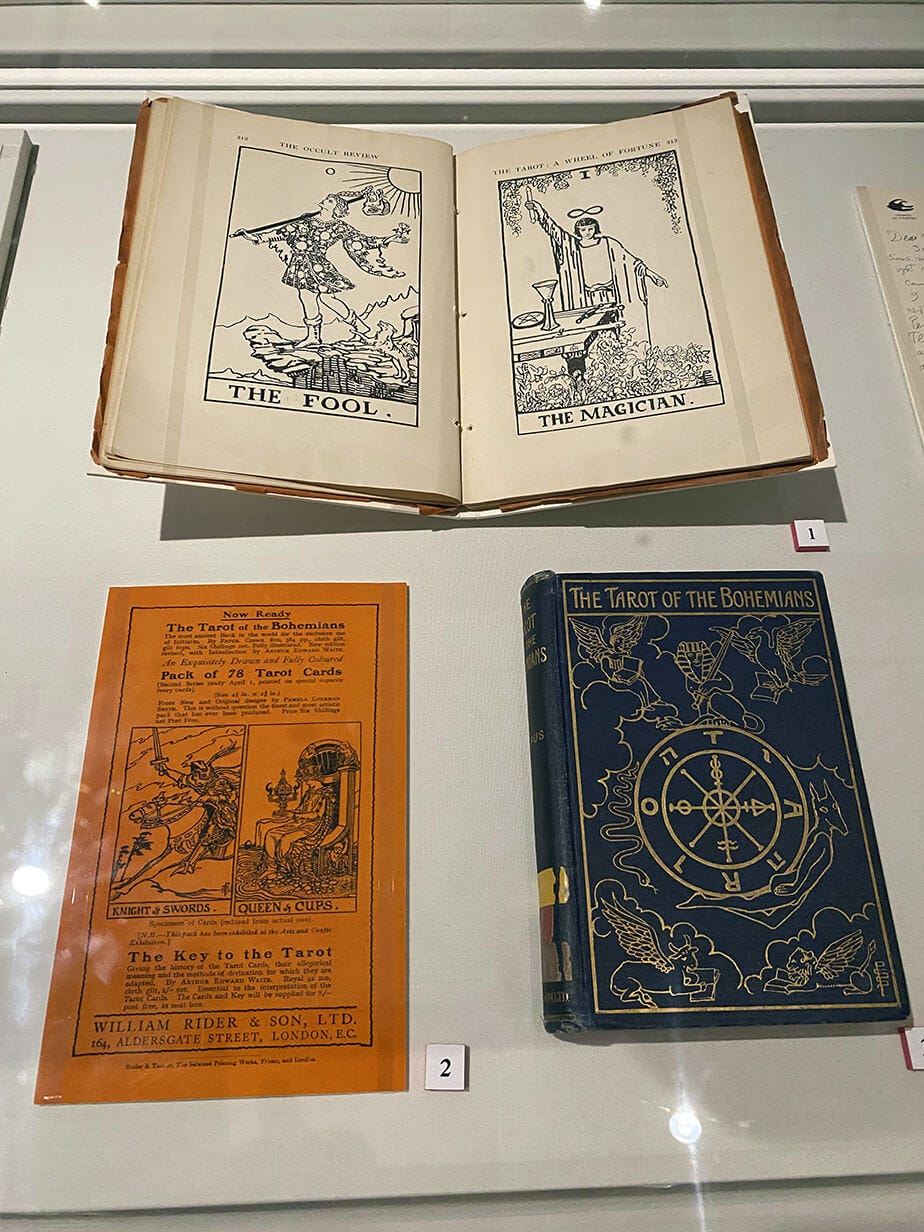

At the Warburg, the next few rooms were devoted to two major 20th-century developments: the invention of the Rider-Waite-Smith tarot and the Thoth cards by Aleister Crowley and Lady Frieda Harris.

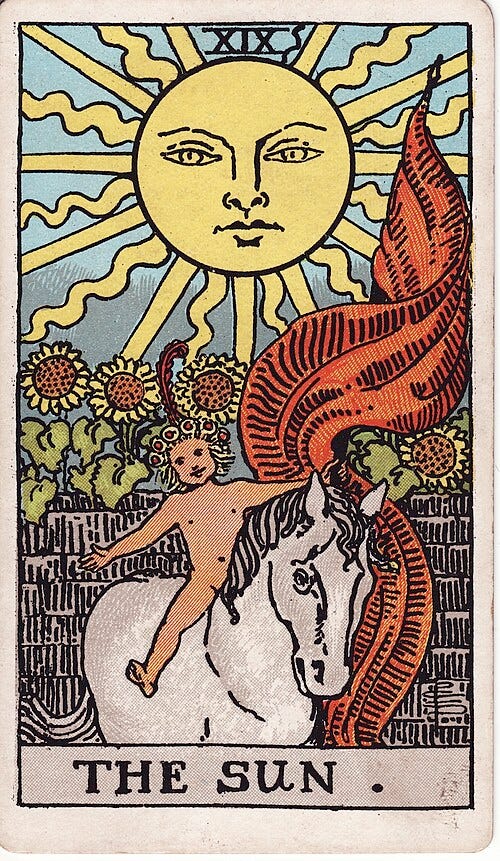

The Rider-Waite-Smith tarot was invented by a Christian mystic, Arthur Edward Waite, and illustrated by the fascinating Pamela Colman Smith - a theatrical set designer who went by the nickname “Pixie”. The drawings were commissioned in 1909 and their deck remains the most widely used one today. According to a contemporary, Smith made a careful examination of the “numerous tarot packs” before embarking on her designs. She was particularly influenced by the Sola-Busca tarot: a Renaissance deck that developed in parallel with the Tarot de Marseille (photgraphs of this deck had been gifted to the British Museum in 1907). The main innovation with Smith’s deck was that the pip cards were illustrative, which made reading them a lot easier for beginners.

While Waite chose overtly Christian imagery (see the Ace of Cups with its references to the communion), Smith evidently had fun depicting her friends on the cards, including the actress Ellen Terry (Nine of Pentacles and Three of Wands) and the theatre director Edith Craig (The Magician). There is also a sprinking of the Egyptian imagery (see the Wheel of Fortune) which had been popularised by Gébelin and the other French occultists.

In 1907, the photographer Alfred Stieglitz gave an exhibition of Smith’s paintings in New York, and it was in a letter to him (on display) that she made her famous remark about her tarot deck being “a big job for very little cash!” Known as the Rider-Waite tarot for many years, Smith is now generally credited along with her co-creator and the publisher, William Rider & Son.5

In the 1930s, tarot took another new direction, thanks to an occult maverick called Aleister Crowley. Like A. E. Waite, he worked with a female artist - Lady Frieda Harris - to create his deck. Also like Waite, Crowley was part of an secret society called The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, which espoused the practice of magic and encouraged initiates to create their own decks for personal use. Other members included Pixie, the poet W. B. Yeats and the novelist Bram Stoker.6

Here the parallels with Waite end, however. Crowley’s deck, The Book of Thoth, is an estoeric system in the vein of Gébelin and Etteilla, with additional layers involving kabbalah, numerology and astrology. After he was introduced to Harris in 1937, she persuaded Crowley to link spirituality and science by the use of projective geometry, which gave his deck a futuristic feel (it was great to see all of Harris’s artwork on display at the exhibition).

After the The Book of Thoth, Crowley went on to found a religion (Thelema) that preached “Do what thou wilt” - for this reason (and others, including his belief in sex magic) the British press branded him “the wickedest man in the world”.

Today, tarot seems a little bit less exciting. We are now in a period where it has become less about divination and more about personal development, a shift that could be seen in the remaining decks on display at the Warburg. As well as a large collection of original artworks from the Hexen 2.0 and Hexen 5.0 decks by Suzanne Treister, there was a small room called the ‘Tarotkammer’ displaying recent decks, some created during the Covid-19 lockdown. If the mark of a good tarot deck is its flexibility, these failed almost universally. Whether it was the Lockdown Tarot, showing Jacob Rees-Mogg as The Devil, or The Alien Sex Club Tarot, showing a man in a cowboy hat removing his trousers, there was little left to the imagination.

Today, we live in a ‘rational’ world, and the superstitions of old are slightly embarassing - but if I could choose any deck from this exhibition, it would be the original one - the Visconti-Sforza. These gilded cards not only look like religious icons, they evoke a lost age of magic and wonder.

Named for the Duke - Filippo Maria Visconti - and his successor, Francesco Sforza.

British playing cards use the French suits - hearts, spades, diamonds and clubs - but the tarot suits are cups (also called chalices), swords, coins (or pentacles) and wands (or batons).

Caitlin Matthews, Untold Tarot (Red Feather, 2018), p. 22. Some of these cards (Justice, Temperance, Fortitude) repesent the Cardinal Virtues, first mentioned by Plato in his Laws.

I’m grateful to Tarot Heritage for this information.

From 1909 until around 1914, Smith was active in the Suffrage Atelier, an artists’ collective which campaigned for women’s right to vote - amongst her other commissions were suffrage postcards satirising Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith.

Crowley fell out with The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in 1902. The story of the occult ‘duel’ - which started with spells and ended with W. B. Yeats kicking Crowley down the stairs - has been entertainingly retold by Mental Floss.

This small essay on the Tarot is fascinating to read and beautiful to see.