Measure for Measure is a play about watchers and those being watched. It’s also a ‘problem’ play (i.e., a play that deals with a problem rather than one that is problematic). It’s a play about justice, and in this regard, the question of who is faithful enough to guarantee the behaviour of others, or can say they are beyond reprimand themselves, is its central problem.

The action is set in Vienna, where Duke Vincentio decides to absent himself, leaving his Deputy, Angelo, in charge of purging the city of vice. Except that Angelo doesn’t practice what he preaches and falls for a young nun, Isabella, from whom he decides to exhort sexual favours. And the Duke doesn’t leave Vienna, either, but disguises himself as a Friar and stays to spy on everything that happens.

Modern readers often puzzle over Vincentio’s motive for handing power to Angelo, but there is an historical precedent in the form of the Duke of the Romagna, Cesare Borgia. According to Niccolo Machiavelli’s The Prince, in 1501 Borgia appointed Ramiro de Lorca, a “cruel, efficient man” to exert his authority over the Romagna, while he sat back and watched. Once the deputy had subdued them, Borgia could continue his rule, all the while blaming his deputy for any cruelty they had suffered (Borgia eventually had his minister killed and his body publicly displayed, which also helped to keep the people “appeased and stupefied”).

Vincentio may be practising a similar kind of realpolitik in Measure for Measure, or he may have other reasons for withdrawing from his rule (let’s not forget that Maria Theresa undertook a similar moral crusade in 18th-century Vienna because she was disgusted with her subjects’ behaviour). We can see from the title of the play - a reference to the Sermon on the Mount: “With what measure ye mete, it shall be measured to you again” - that the play focusses on divine retribution. While he doesn’t mention the Bible specifically, Shakespeare puts an echo of Christ’s words into the mouth of Vincentio during the mad finale:

…death for death.

Haste still pays haste, and leisure answers leisure;

Like doth quit like, and Measure still for Measure.

Rather than the Bible, I think there’s an even clearer parallel with that famous line from Juvenal’s Satires: “Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?” (VI). The original context for this quotation (often translated as “Who will guard the guards themselves?” or “Who watches the watchmen?”) refers to the issue of preventing a wife from being unfaithful. However, it has come to mean the problem of controlling the actions of those in positions of power.

The designation of Measure for Measure as a comedy is quite at odds with its weird distastefulness. Harold Bloom regarded it as a work of “high rancidity” and described it as “Shakespeare’s goodbye to comedy” (it was also, incidentally, one of Bloom’s favourites). On my first read-through I found the recurring images of coins to be quite curious. Angelo’s remark to the Duke: “Let there be some more test made of my metal, before so noble and so great a figure be stamp’d upon it” is just one example (elsewhere, he talks of “[coining] heaven’s image in stamps that are forbid”). The language in the first half of the play is stark and preoccupied with currency and exchange.

This is because Angelo and Isabella are essentially cold characters who see everything in black and white terms. In other words, they’re both extremists: Isabella is a noviciate who wishes for “a more strict restraint”, similar to that practised by the nuns of St. Clare (a white-habited order), while Angelo (who has taken over the government of Vienna from the absent Duke) is obsessed with sexual transgression. What drives the plot is Angelo’s decision to make an example of Isabella’s hapless brother, Claudio, who has got his girlfriend pregnant out of wedlock. Claudio is sentenced to death, but the “watcher’s” morals prove to be less than pure; if Isabella sleeps with Angelo, he will let her brother live (this is a familiar plot-type known as the ‘monstrous bargain’).

Angelo and Isabella initially seem to be quite similar. Like two coins, they look the same, but it’s what underneath that matters. While Isabella is pure silver, Angelo is base metal: a counterfeit. At the time Shakespeare was writing, people would have been familiar with the process of testing the metal of coins for purity, namely, melting them down in a crucible. It’s only when we are tested in the crucible of temptation that our true natures reveal themselves.

The Duke is a character who frustrates our attempts to understand him. He professes to dislike the scrutiny of his subjects but enjoys watching them; he spends most of the play disguised as a Friar, giving people his own brand of (fake) religious counsel. He whips the plot into a mass of knots which only he can unravel, leaving us bewildered. Is the Duke a good leader or is he another whited sepulchre?

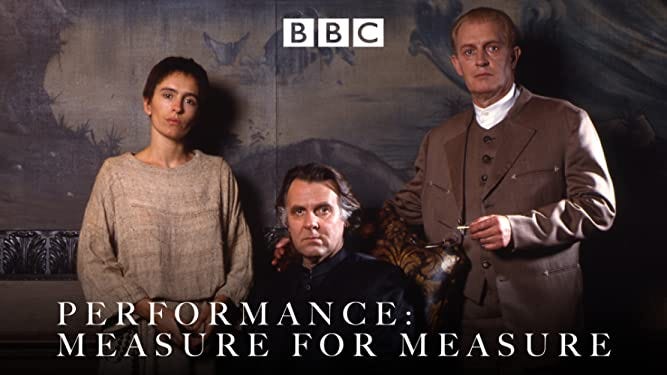

The conclusion of David Thacker’s 1994 filmed version for the BBC (with the late Tom Wilkinson as the Duke) made me rethink this character as another extremist. Driven by his own passion for Isabella, he tips over into a sadistic ringmaster, obsessed with himself as the plot’s deus ex machina. Isabella is wedded to Christ, but the Duke wants to impress her by playing God. His “happy ending” is so abhorrent that he ends up looking just as bad (perhaps worse) than Angelo.

Meanwhile, the RSC’s 2019 production, directed by Gregory Doran, has been dubbed the #metoo version, with Lucy Phelps’s Isabella projecting a painful sense of physical disgust, even when Angelo’s attempts to seduce her are thwarted. She represents a traumatised victim of sexual abuse, while Sandy Grierson’s Angelo is a sadist and – to modern minds – a religious fanatic (he keeps his legs bound in chains, much as Thomas à Becket wore a hairshirt under his archbishop’s garments). The Duke (Anthony Byrne) is a damaged individual; when the play opens we discover him in his mirrored ballroom, apparently in the throes of an anxiety attack. Both his Friar’s disguise and his attempts at comforting his subjects are careless, ill-conceived and irresponsible.

What can be done about corruption at the top? This is the central question of Measure for Measure, and Isabella’s cry of “Justice! Justice! Justice!” resounds across the whole piece. Shakespeare doesn’t go in for comforting platitudes, and the concluding scene of the play leaves us reeling with shocked disbelief. The truth of the matter is that, faced with injustice, sometimes we are gagged; sometimes the powerful block us. Sometimes good fails and language is inadequate.

Who will watch the watchmen? Only God sees all.

Thank you Annette for another brilliant article on a Shakespeare’s masterpiece.

Personally, here I saw the human blindness in lack of discrimination/wisdom.

Also, found interesting that power is portrayed as a complete illusion here—the duke gives up his duties (albeit not entirely) and remains in a kind of limbo. Angelo thinks he’s powerful but he is a slave of his own twisted desires.

To me the title seems almost ironic on how the lack of an inner “measure” takes away freedom here.

I wonder whether this was disliked by some critics because they did not like to hear this…