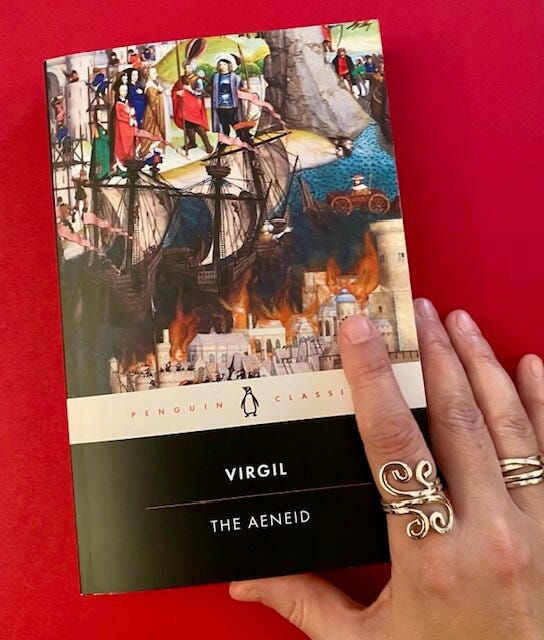

I would describe The Aeneid as one of those books which I didn’t always enjoy, but I’m glad that I read. I think part of my problem with this book was David West’s prose translation, which I found a bit flat. On the positive side, it was very clear and the scholarly notes - short synopses of each book - were handy (I read them after I’d finished each Book). Overall, I think the Penguin version is a decent entry-point into Virgil’s world, but if I were to pick The Aeneid up again, I would probably choose a poetic translation.

What I did take away from the experience was an appreciation of the cultural richness of Virgil’s work. Certain books of The Aeneid (for example, the story of Dido and the hero’s descent into the Underworld) are rightfully classics and it was great to access the source material which inspired, for example, the player’s speech in Hamlet or Purcell’s opera Dido and Aeneas. As someone said to me: “When Virgil is good, he’s really good” and that gets you through the slog of the less exciting passages (my least favourite was probably Book 5: The Funeral Games). I didn’t find it particularly exciting to read frequent roll-calls of Roman names, either, but as West points out, these are important to Virgil’s aim, namely to create a foundational myth for Italy.

I took my copy of The Aeneid when I went to Rome, because I find it helps my understanding and appreciation of literature if I can weave it into my daily life. With Shakespeare, for example, I employ what I call a ‘three reads’ method. It goes like this:

Read the play.

Read an essay or listen to a podcast about it.

Watch a performance (live or on DVD).

By the time I have done those three things, I am pretty immersed in the material. In the case of The Aeneid, I combined reading the text and reading West’s synopses with a trip to see Bernini’s statue of Aeneas, Anchises and Ascanius, fleeing Troy, which is on display at the Borghese Gallery in Rome.

The story I’m talking about is taken from Book 2, which deals with the fall of Troy (the following quotes are from the West translation).

The hero, Aeneas, tries to rescue his family from the burning city, but his father, the shepherd Anchises, feels defeated and asks to be left behind to die. Yet, at that moment, they witness an omen: a halo of fire suddenly appears around the head of Aeneas’s son, Ascanius (also known as Iulus - confusingly, Roman men had at least two names). This sign from the gods convinces Anchises to leave with his family:

The noise of the fires was growing louder and louder through the city and the tide of flame was rolling nearer. “Come then, dear father, up on my back. I shall take you on my shoulders. Your weight will be nothing to me. Whatever may come, danger or safety, it will be the same for both of us. Young Iulus can walk by my side and my wife can follow in my footsteps at a distance.”

Because Aeneas is famously pious, he directs his father to “take in your arms the sacraments and the ancestral gods of our home”. The household gods need to go with them because Aeneas is destined to found a new race in Latium, the future Italy. You can see how Bernini included them as two sculptural figures on a miniature pedestal. These are the Di Penates (gods of household provision) which were among the Roman dii familiares (household deities) invoked in acts of domestic worship. The Di Penates were particularly associated with the virgin goddess, Vesta (you can find out about my own dii familiares in this post).

Unfortunately, I didn’t get much time to examine this sculpture, since our time slot at the Borghese was up - but just look at the tense, determined expressions on their faces. In the first photo you can see little Ascanius/Iulus sticking close to his father; he carries the eternal flame from the Temple of Vesta in his hands (which is how we know that Anchises is carrying the Di Penates).

What I find amazing is the fact that Bernini was only 19 when he sculpted this group of figures; the spiralling form suggests a Mannerist influence, and because of it, people have mistaken the work for that of Bernini’s father, Pietro. That’s ironic because the sculpture is all about fathers and sons (also a key theme of The Aeneid) - it shows how the hero’s personality combines both strength and tenderness.

In fact, when I read the above passage for the first time, it reminded me of Shakespeare’s Orlando in As You Like It, particularly the scene with Old Adam in Act Two, Scene Six:

Adam. Dear master, I can go no further. O, I die for food! Here lie I down, and measure out my grave. Farewell, kind master.

Orlando. Why, how now, Adam! No greater heart in thee? Live a little; comfort a little; cheer thyself a little. If this uncouth forest yield anything savage, I will either be food for it or bring it for food to thee. Thy conceit is nearer death than thy powers. For my sake be comfortable; hold death awhile at the arm’s end. I will here be with thee presently; and if I bring thee not something to eat, I will give thee leave to die; but if thou diest before I come, thou art a mocker of my labour. Well said! thou look’st cheerly; and I'll be with thee quickly. Yet thou liest in the bleak air. Come, I will bear thee to some shelter; and thou shalt not die for lack of a dinner, if there live anything in this desert. Cheerly, good Adam!

That bit where he says “I will bear thee to some shelter” suggests he lifts the old man up on his shoulders, much as Aeneas does with Anchises. I wonder if this part of The Aeneid was in Shakespeare’s mind when he wrote that scene.

Do you have a favourite translation of The Aeneid? Please let me know in the comments!