I studied Othello in the early 1990s, but I can’t say - young as I was - I really understood it. Now, having returned to it for a long overdue re-read, I found it to be a profoundly unsettling play, as difficult to face as King Lear and as relentlessly nihilistic as Macbeth.

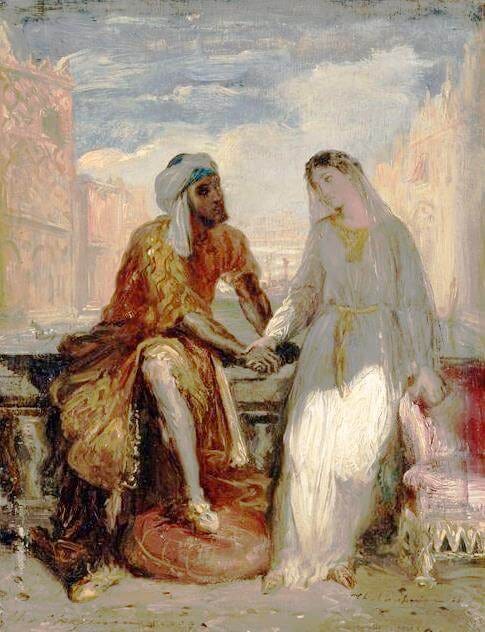

For those who haven’t read it, the plot follows Iago: a Venetian ensign who serves the noble Moor, Othello. The latter is head of the Venetian state and married to Desdemona: a virtuous beauty who has married him against her father’s will. Iago, having been passed over for promotion in favour of Cassio (a Florentine aristocrat) decides to revenge himself on his rival and on Othello, whom he also hates. He does this by pretending that Desdemona and Cassio are having an affair, and he poisons Othello’s mind until he is so enraged by jealousy that he strangles his innocent wife.

There has been reams written on Iago and his motivations which I don’t intend to focus on too much here, except to say that Shakespeare gives him phrases of extraordinary emptiness - lines that sound impressive, but, under close inspection, reveal themselves to be meaningless. There is a dramatic problem with this - Iago takes up most of the play but the poetic speeches are all reserved for Othello: the noble character. I found it uncomfortable spending time in Iago’s head (he has eight soliloquies compared to Othello’s three) - and, oddly, I haven’t felt this repulsion while watching the play, only reading it.

There are touches of hope, though, and I wanted to concentrate on one of them: storytelling. If we think back to the start of the play, it’s Othello’s amazing stories of his adventures which first attract Desdemona to him:

It was my hint to speak, such was the process:

And of the Cannibals, that each other eat;

The Anthropophagi, and men whose heads

Do grow beneath their shoulders; this to hear

Would Desdemona seriously incline;

Storytellers are seducers. Let’s look at how Othello explains the importance of his first gift to Desdemona - the handkerchief spotted with strawberries, which she thinks she has lost and he thinks she has given to her lover:

… that handkerchief

Did an Egyptian to my mother give,

She was a charmer, and could almost read

The thoughts of people; she told her, while she kept it

‘Twould make her amiable, and subdue my father

Entirely to her love: but if she lost it,

Or made a gift of it, my father’s eye

Should hold her loathly, and his spirits should hunt

After new fancies …

Now, at this point in the play, he is enraged over this missing handkerchief, and his tale about its symbolic importance is a trifle overdone. This is precisely, of course, what Iago would do: there’s a fine line between spinning a tale and lying, and Iago is a master of “seeming” - making the outward appearance of things tell a different story to their inner truth. At the play’s climax, Shakespeare pulls the carpet from this particular piece of “ocular evidence” and shows us how much Othello has been influenced by Iago’s fictions. Explaining his actions to Emilia, who has discovered the dead body of Desdemona, Othello says:

It was a handkerchief; an antique token

My father gave my mother.

So the stuff about the Egyptian was not true - just a piece of manipulation to make his wife feel even more terrible (isn’t this what jealousy does to us - tries to make us wound the other person?) What’s heart-breaking about Desdemona is that she’s incapable of duplicity. When Othello is about to smother her, she simply pleads:

Kill me tomorrow, let me live to-night.

This line reminded me of that other tale of marital disharmony and storytelling: the Arabian Nights. In it, the ruler Shahryar, on discovering that his first wife was unfaithful to him, resolved to marry a new virgin every day and to have her beheaded the next morning before she could dishonour him. Eventually he runs out of willing candidates and Scheherazade - a woman extraordinarily witty and wise - reluctantly agrees to marry him. On their wedding night, Scheherazade begins a tale but does not end it. The king, curious to know the conclusion, postpones her execution - and the next night, though she finishes the first tale, she begins another one, and so on for a thousand and one nights.

We have an echo of Scheherazade’s exotic tales in Othello’s final speech, which is full of what G. Wilson Knight called the “Othello Music”:

… then you must speak

Of one that lov’d not wisely, but too well:

Of one not easily jealous, but being wrought,

Perplex’d in the extreme; of one whose hand,

Like the base Judean, threw a pearl away,

Richer than all his tribe: of one whose subdued eyes,

Albeit unused to the melting mood,

Drops tears as fast as the Arabian trees

Their medicinal gum ..

This is the poetry we have been waiting for and it’s a moment of divine beauty - a liebestod of the type we get at the end of Tristan and Isolde. Compare the poverty of Iago’s final line, expressing the complete blankness of his soul:

Demand me nothing, what you know, you know,

From this time forth I never will speak word.

I recently read Harold Bloom’s essay on Othello in his Shakespeare and the Invention of the Human. I know Bloom isn’t to everyone’s taste but I have a ritual of reading his corresponding essay once I have finished one of Shakespeare’s plays. I don’t always agree with him (especially his bizarre insistence that Shakespeare didn’t write Christian drama) but I like his pungent take on things, and he had good insights.

Regarding this play, I tend to agree with Bloom that Othello is a “self-enchanter” who exhibits “a powerful romance of the self” - in other words, he has constructed an identity that is based on a story of himself as a heroic warrior. To be generous, we might say that this ‘heroic self’ helps Othello to do his job, leading men into battle. Yet it’s precisely because he’s seduced by his own stories that Iago is able to manipulate his general so easily.

While Othello thinks too romantically of himself, Iago has no inner life at all. His speech in Act I, Scene iii is the closest we get to a world-view:

Virtue? a fig! ‘tis in ourselves, that we are thus, or thus: our bodies are gardens, to which our wills are gardeners, so that if we will plant nettles, or sow lettuce, set hyssop, and weed up thyme; supply it with one gender of herbs, or distract it with many; either to have it sterile with idleness, or manur’d with industry, why, the power, and corrigible authority of this, lies in our wills. If the balance of our lives had not one scale of reason, to poise another of sensuality, the blood and baseness of our natures would conduct us to most preposterous conclusions. But we have reason to cool our raging motions, or carnal stings, our unbitted lusts; whereof I take this, that you call love, to be a sect, or scion.

Bloom calls the above Iago’s “economics of the will” - a sort of manifesto against empathy. The conversational blank verse (presented as an unrelenting block of text in my facsimile of the First Folio) shows how unpoetic his nature is, and the supreme irony of this speech is that Iago uses Othello’s body as his garden, where he plants nettles.

I recently watched the 1995 film version of Othello with Laurence Fishburne as Othello and Kenneth Branagh as Iago, which I liked. Branagh is such a genial actor that he made for a seductive Iago - the character must be a little charismatic, I think, to be given the repeated epithet “honest” by his colleagues. Anyway, what I liked about Branagh’s performance was his subtle indication that Iago loves or perhaps even wants to be the Moor. He suggests this during the pivotal scene in Act 3 Scene iii, when Iago swears he will commit himself to “wrong’d Othello’s service” by killing Cassio, and Othello replies: “now art thou my lieutenant”. The scene is staged as a kind of blood brotherhood ritual, in which they cut their hands and clasp them together. As they embrace, we see over Othello’s shoulder the first evidence of authentic emotion from Iago, whose eyes are filled with tears as he replies: “I am your own for ever”.

The tragedy is that, in the end, it’s not really a case of Iago becoming Othello’s “own”, but Othello being possessed by the “demi-devil” Iago. I found the references to Othello’s epilepsy curious and some Googling revealed that in the Medieval period it was thought that the ‘falling sickness’ was an indication of demonic possession (you will notice that Othello cries “O devil!” before falling into an epilepsy). The play closes with a horrible mirroring - both men murder their wives - but we hope that Othello won’t be judged as harshly by heaven because, like “the base Judean” (a reference to Herod who killed his beloved wife Mariamne out of jealousy) he was not in his right mind, whereas Iago knew what he was doing all along.

Much more disturbing was seeing Paul Scofield do blackface.

There be no line lass

No line at all between

Seducing and lying, no

Line at all, not or ever so

Much as that which might

Amount, should it exist, to

Being suggestion of a fine

Line: "I speak to conquer, and

having conquered let's to bed,

and wed early tomorrow so as to

be sure we can sup sorrow with it's

longest spoon henceforth and even

evermore as long as we both may live

and breathe. That's all, save to say Amen!"