This is a continuation of our walking tour (first published in 2009) using Dr William Moss’s 1797 guide to Liverpool. If you haven’t joined us already, you can as start here.

At this point in our Liverpool journey we deviated from Dr William Moss's guide book and walked over to Rodney Street: an area filled with fine Regency terraces. This and the surrounding streets can certainly compete with areas of Bath and Dublin for beauty and authenticity, and it's amazing that they aren't as well known. Here we took a short detour to see St Andrew's Presbyterian Church, built in 1823 and once described as 'an ornament to the town'.

Below is my picture of its current dilapidated state. Most of it has been shored up to avoid accidents (the left tower has been removed entirely). At some point it was gutted by fire, and gives off a sad atmosphere.

As we were peering through the fence at the graveyard, I spotted this strange pyramid tomb (below).

I did wonder if it was Masonic, but it was only later I discovered it's the tomb of William Mackenzie: a wealthy Victorian railway engineer and Liverpool's most notorious gambler. As the story goes, Mackenzie - hoping to win at poker - had promised his soul to the devil. He won the game, but falling ill shortly afterwards, began to fear that the devil would demand his part of the bargain. So with his winnings he constructed this tomb, leaving instructions that his card table and chair should be placed inside. He's supposed to be interred seated at the table holding the winning cards, thus cheating the devil out of his Faustian pact (presumably because his body was not in the ground). Mackenzie is said to haunt Rodney Street, so that explains the eerie, sad feel of the place!

There’s more on the tomb here.

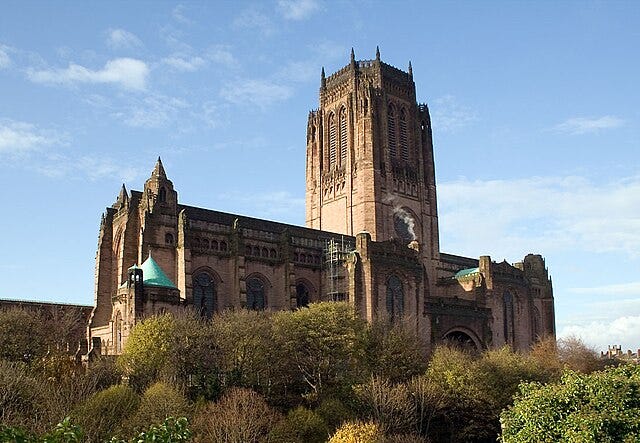

Having enjoyed our detour down Rodney Street, we thought we'd take a look at the Gothic Anglican Cathedral, which is futuristic by Dr Moss's guide book's standards, having been built between 1904 and 1978.

You can see what an imposing edifice it is (it was freezing cold and getting towards dusk when I took the photograph above, and the steam issuing out looked especially eerie). What we particularly wanted to see, however, was The Oratory (below), which stands at the front of the cathedral, beside the descending pathway into St James's Cemetery.

This is the cemetery's former chapel; its purpose was to accommodate funeral services prior to actual burial, and it also housed monuments to the dead. It was designed by John Foster (1786-1846) in the Greek Revival style, though sadly, the burial ground has since been abandoned. We couldn't get near it because it's fenced off, but you can view the interior on appointment (EDIT: it’s now in the care of National Museums Liverpool but is closed to the public).

After a look around the graveyard, we emerged up the other side of what's known as St James's Mount, a ridge overlooking the city. We were just about to leave when my boyfriend spotted a little grassy area which caused him to pause and flick through Dr Moss's guide (below).

We'd come across St James' Walk: an area developed in 1779 as a place of fashionable amusement. It was half-covered in undergrowth (not to mention the cathedral itself, which, as you can see from the picture below, was built partially on top of it), but the pathways were unmistakeable.

Here we are standing at the entrance to the walk, which Dr Moss describes as: 'a gravelled terrace, 400 yards long. It has been compared to the terrace at Windsor. From hence we have a very extensive prospect, across the Mersey, of the north part of Cheshire'. The view is still pretty splendid today, though clearly not as extensive. Moss adds that you were obliged to enter on foot because a horse-block was placed near the entrance.

Below is the view looking back at the ‘entrance’ from the terrace. Moss's modern author/editor, David Brazendale, adds that: ‘Some visitors came in search of the mineral spring which had been discovered in the rock wall of the quarry [i.e., St James's Cemetary] and which was reputed to be beneficial in the treatment of eye infections.’

A glimpse through a gap in the hedge revealed a tree-lined walks reminiscent of the pleasure gardens of the 18th century. We were pretty excited by the discovery of this ‘engaging spot’ and the knowledge that this is probably the closest we'll get to visiting Vauxhall or Ranelagh, though of course, St James’s Walk wouldn't have quite been on the same scale!

This is the end of our formal tour, but as some of the buildings were so interesting (I haven't even mentioned the Lyceum and the Catholic Church, which is now the Alma de Cuba nightclub) I plan to do a couple of isolated posts on them. I hope you enjoyed my guide to Georgian Liverpool in the year 1797.

Which of the now, trying to count even as I type and realise that they are more numerous than the constellated stars on a clear bright firmament night, umpteen ghosts that are, since I posted my reply, clamouring to be auditioned should will cast in the leading part of Protagonist?

You have set me wondering Annete even as I romble on into this all too typically dull Middle English, early in September, morn.

A timely post, what with today being the first day of September, a moment in the time of this year's paced passing and a Part II which likely sets some looking up ahead along the paths they're treading towards the ushering in of Autumn with all its attendant mists and mellow fruitfulness.

It's reference to The Oratory that's most saliently catching my attention, by putting me in mind of the tomb in which Lincoln's son Willie was interred, in Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington's Georgetown. Could, I wonder, there be ghosts of the kind envisaged by George Saunders in bringing 'Lincoln in the Bardo' in and onto his writing pages, from whatever void his novel story came from?

In the wings of my Sunday imagination I sense there could, very well be, stirring of such "ghosts" that inhabit the Bardo "disfigured by desires they failed to act upon while alive" who are threatened by permanent entrapment in the liminal space... unaware that they have died, referring to the space as their "hospital-yard" and to their coffins as "sick-boxes". *

Egad but typing that quote - and thinking about that MacKenzie, Entreprenuerial Engineering Esquire said to sat upright still in his pyramid-tomb long dead but bidding his crafty cardplay can eternally cheat and beat the Devil while, in times present, he routinely takes his constitutional haunting stroll about Liverpool town - has set waves of goosepimples running out from the base of neck and pulsing through me with electrifying effect!

Who knows but that reading your Lichfield Rambling post has spawned the first sparks of a seasonal ghost story, striving to form and break out from it Georgian setting?