Whereas even those with a casual interest in the history of British theatre would recognise the name David Garrick, Charles Macklin’s contributions to the development of acting have been all-but forgotten. An 18th-century celebrity, Macklin was an early mentor of Garrick’s and worked alongside him on the London stage for several decades; his influence on such diverse areas as theatrical management, Shakespeare in performance, dramatic instruction and intellectual property are all worthy of further investigation.

Macklin did have one major advantage over Garrick: longevity. As this essay-collection shows, his stage career (begun around 1725) stretched from the reign of George I to the Regency Crisis of 1788, giving him a unique perspective on the development of 18th-century theatre. Macklin – frequently hot-tempered – was embroiled in legal cases throughout his life, the most serious being in 1735, when he accidentally killed an actor in a back-stage quarrel.

This unfortunate incident would come to define him. It happened at Drury Lane, just before a performance of R. Fabian’s Trick for Trick, in which Macklin shared the bill with an actor called Thomas Hallam. Having found Hallam in possession of a favourite stock wig, an argument broke out between the two men, during which Macklin lunged towards the actor with his cane in his hand. Unluckily, as he did so, Hallam turned towards Macklin and the point of the cane went into Hallam’s left eye. Despite the victim’s bizarre request to ‘urine in my eye’ (it was an 18th-century belief that urine and spittle were proper remedies for wounds), Macklin’s cane had pierced the poor man’s brain. He quickly fell into a wretched state and died at six o’clock the following morning.

Terrified, Macklin went into hiding, but found an ally in Drury Lane’s manager, Charles Fleetwood, who persuaded him to stand trial for murder. During the court case, Fleetwood and others stated, with some creative license, that Macklin was ‘a man of quiet and peaceable disposition’. Macklin spoke in his own defence (lawyers were not yet familiar figures in criminal trials), and the jury accepted that Hallam’s death was accidental, returning a verdict of manslaughter. Macklin was sentenced to be burned in the hand – a token punishment, probably carried out with a cool iron – while all eleven of his fellow defendants at the Old Bailey that day were sentenced to death.

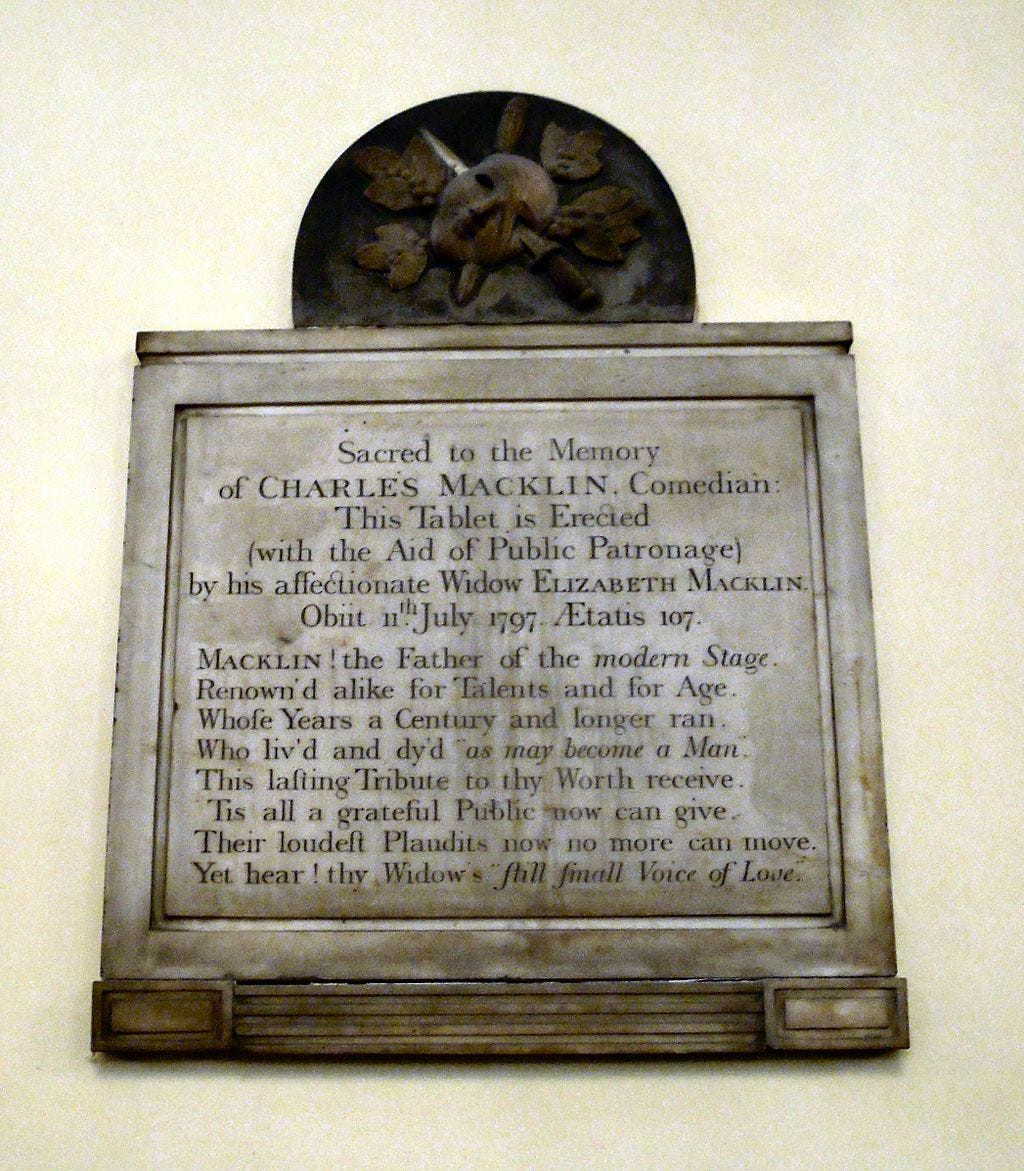

This incident was never forgotten, either by Macklin, Fleetwood, or by the theatregoing public; in fact, visitors to St Paul’s Church, Covent Garden, will find Macklin’s memorial embellished by a theatrical mask with a dagger piercing one eye socket (above).

However, the spectre of Macklin’s violent dispositon would prove useful in 1741 when he played Shylock in The Merchant of Venice. Before this period, Shylock was usually played as a comic grotesque with a red wig, but Macklin brought both ferocity and realism to Shylock, re-shaping the role into something closer to modern ideas of it. He was apparently so terrifying as Shakespeare’s moneylender, his performance gave George II a sleepless night.

As with many 18th-century figures, Macklin’s life encompassed a variety of interests, and it was good to see so many of them represented in this book. David Francis Taylor’s absorbing essay, Macklin’s Look, not only charts how the actor’s body was read on-stage but examines Macklin’s Shylock as the “bogeyman of Georgian culture” – ghosted by memories of Hallam’s murder (31). Other richly rewarding topics include a chapter by Paul Goring on Macklin’s book collection, in which the actor’s “Enlightenment credentials” are examined alongside his status as both player and autodidact (69-70). In “Strong Case”: Macklin and the Law, David Worrall explores the extent of the actor’s legal knowledge (I was fascinated to learn how Macklin’s lawsuit over a pirated version of his play Love à la Mode became a cornerstone of early copyright law).

However, I was less convinced by Michael Brown’s assertion (in Ethnic Jokes and Polite Language: Soft Othering and Macklin’s British Comedies) that Macklin’s Scotophobia was the result of “Competitive Celtism” and felt an analysis of the Plantation of Ulster and its impact might have been missing (182).

Nevertheless, the volume closes with two essays about recent stagings of Love à la Mode, which happily brings theatre practitioners into the debate. The final chapter is a discussion between Nicholas Johnson (Associate Professor of Drama at Trinity College Dublin) and Colm Summers (Theatre Director) about the practicalities of staging Macklin, all lavishly illustrated with colour plates. There’s much to like about this multi-faceted approach (which also includes an excellent introduction by Ian Newman and David O’Shaughnessy), and, while understanding Macklin’s long and diverse career is a challenge, Charles Macklin and the Theatres of London is a splendid and much-needed start.

Charles Macklin and the Theatres of London

Ian Newman and David O’Shaughnessy (eds.)

Liverpool University Press, 2022

£95.00 hb., £24.95 pb and e-book, 344 pp.; 23 b/w, 8 col ill.

ISBN 9781800855984; 9781800856912; 9781800855601